The Roadside Hunters: Lessons from Ditch Chickens, Pop Bottle Hunting, and Trading Cards

By Tony Rustad

The glint of sunlight on the green glass butt of the 7-up bottle captured a momentary emerald sparkle as it protruded through weeds and grass at the waters edge of the roadside ditch. I stealthily crept forward, on hands and knees. But in that lapse of attention while I was observing the unnatural jewel set partially under water amongst the green and golden strings of dead grass and black gumbo along the edge, the fist sized bull frog I had been watching carefully, suddenly leapt into the warm pool and disappeared. Despite the unusually amber clarity, the visual acuity was warped of the reflection of the sun off the circular ripples caused by the splash and the unusually large amphibian squeezed into a hidden pocket somewhere beneath.

"Ditch chicken! He just disappeared to his hideaway. Raymond, Come're en help me watch, he'll come back up again. That was the biggest ditch chicken I've ever seen. His legs were like this." I showed Raymond my index finger and thumb in a circle representing a plump thigh, unlike most of the medium sized frogs we had already collected. It was the middle of the summer and the frogs had grown large enough so eight or ten of them made a nice meal for one 6 year old and one seven year old boy. They would soon be pan fried like chicken, in butter or Crisco, on a home made brick grill in the dirt alley between Rustad’s and Tri's . We would soon be sharing our main meal, along with a quart mayonnaise jar of cherry Kool-Aid and a bag of Old Dutch.

"How bout if I throw this ole bottle at em." I said as I raised the 7-up bottle out of the ditch bottom, draining its contents in the grass so as not to disturb the water.

"It's too deep, we might lose it. My mom will give me a tanning if I get wet again today. Sides, Mayme will give us 3 cents a piece for any pop-bottle we bring in. Have you ever brought her bottles? She's real good."

"Any bottle?"

"Naw, Just pop-bottles."

"Three cents a-piece."

"Three Cents"

"Share."

“Share.”

The roadside hunters found game and other valuable bounty, worthwhile nougats, and bits of experience with which they would ever be grateful.

Telling this story to a colleague at the financial services firm where I'm now employed, ignited memories and experiences about growing up in our rural Midwest towns. He also recalled learning specialized skills in his youth, becoming an avid roadside hunter and trader. Decades have passed and later generations of children have missed the opportunity of earning real money by marketing discarded bottles. Yet for me, it was pop bottle collecting that was the genesis of a frugal career in marketing and trading.

Telling this story to a colleague at the financial services firm where I'm now employed, ignited memories and experiences about growing up in our rural Midwest towns. He also recalled learning specialized skills in his youth, becoming an avid roadside hunter and trader. Decades have passed and later generations of children have missed the opportunity of earning real money by marketing discarded bottles. Yet for me, it was pop bottle collecting that was the genesis of a frugal career in marketing and trading. |

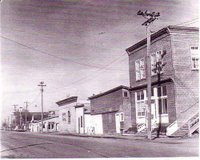

| Click to Enlarge. You can see Elmer in the shade [Photo: David Stewart] |

Mayme Jury’s store represented the high end of the business. She used more discretion in purchasing bottles, rejecting those containing chips and cracks, flaws which inevitably destroyed all commercial value. Mayme, who was a kind but practical business person, quickly pointed out: “We purchase the bottles as a service. It is a small monetary remuneration in lieu of the previously paid deposit given when the bottles of soda were originally purchased. I'm not really a bottle dealer.”

Mayme Jury’s store represented the high end of the business. She used more discretion in purchasing bottles, rejecting those containing chips and cracks, flaws which inevitably destroyed all commercial value. Mayme, who was a kind but practical business person, quickly pointed out: “We purchase the bottles as a service. It is a small monetary remuneration in lieu of the previously paid deposit given when the bottles of soda were originally purchased. I'm not really a bottle dealer.”Mayme always willingly provided the incentive for clean and flawless bottles, ringing up the full three cents deposit. The small, kind, elderly proprietor always measured her speech, carefully noticing intricate details that a business person should be aware of. She was personally clean and carefully groomed. Like my grandmother and many middle aged women in that age, her graying hair as wrapped in a bun on the back of her head. Her thin black glasses covered sparkling eyes. Mayme did not often frown.

Mayme also had a penchant for remembering each child's name and saying it often. She cared deeply for the welfare of her clientele and warmly received each child who entered her store. She asked to know each detail that the children shared about their lives and often remembered to allude to earlier conversations with them. Children were trusted to go behind the counter to the candy shelves and hand choose the tasty selection. This custom was among carefully formulated, clear and understandable guidelines about our conduct in her domain. Children did not take candy without paying for it, and Mayme's voice did not have to become harsh. Mayme’s method of redeeming pop-bottles insured that she would be reimbursed for every bottle she purchased from the children of the village of Humboldt. The condition of the bottles and which brands she would accept were quite understood and often repeated. Mayme’s rule of reason had the virtue of being a bright-line model easily understandable by every Humboldt kid in the 1950s and 1960s.

The bottles that Mayme refused could often be sold to Elmer Maxwell, whose business model was not based upon profit maximization. Elmer, the gentle proprietor of the little Standard gas station on the North side of town, would open a worn leather purse to produce two cents for each of the bottles. The kind and demure old man seemed heedless to their condition. He often took time to have a mature conversation with us: “Say, how bout that Whitey Ford. Do you think there' s any better pitcher in baseball.” Sporting News says he'll lead the Yanks to another pennant.

“Warren Spahn's my favorite.”

“Is that so. Are the Braves your favorites? That Aaron and Mathews are almost as good as Mantle and Yogi. I have something to show you.” Then Elmer would amble into the shack and point to an article or a statistic in his favorite magazine (Sporting News). As I reflect back, I know we were his closest acquaintances. He purchased every bottle even if they appeared to have been retrieved after lying for a decade in the swamp water of a ditch near town. Elmer’s humble gas station was formerly a tar-hut railroad car placed only about fifteen yards in front of his home on Highway 75 near the north side of Humboldt. Elmer’s Standard Oil franchise did not have a bathroom, but if you asked he would let you use his outhouse. His station had so little clearance between the pump and his shack that a large car would refuel with great difficulty. Elmer kept his returnable bottles out in the open, haphazardly stacked in wooden Coca-Cola crates on the south side of the station hut. Some of those bottles remained there for many years and were obviously never redeemed. I recognized some of them from the distinguishing flaws. Decades later, I recalled a memory of a specific Nesbitt orange bottle by the chips of glass on the rim and a Canadian dry bottle by the cracks on its characteristic thick bottom side. Elmer’s business model was built on good will rather than fastidiousness. Only rarely did the white haired old gentleman press the appropriate discount because of the depreciated market value of a chipped bottle was lower than a clean and perfect bottle. Many were worthless. He often purchased bottles found on roadsides that had originated from neighboring Canada, glass that would eventually become an ornament memory of his generous nature.

Thus, the bottle market then consisted of two principal buyers with different criteria for cleanliness and condition. My response to this bifurcated pop bottle market was to clean all of the bottles to the best of my ability for the return of earning three cents per bottle. From this early experience with pop bottles, I learned the value of economy and time management in cleaning them. Among my earliest memories of the roadside hobby were the occasions I found a half-full ditch of semi-clear water where I quickly discovered I could clean the bottles most efficiently. The work was enhanced by the ambiance of the countryside, the amber colored water reflecting the sun and making the plants, small stones, and insects appear as jewels sparkling on the bottom of the ditch. I plunged the bottle into this warm and enticing pool, filling it half full. Then I inserted my index finger into the opening until it almost formed a plug. When I shook the bottle, it often resulted in the tepid water spraying in my face and over my clothes. I viewed this as a cost of doing business. I attempted to reduce this problem by developing a better technique for cleaning the bottles. Eventually, I fell upon the most efficient method, which was to plant my thumb squarely over the lip of the bottle and then shake it with all my might. That generally loosed the particles of dirt and unidentified debris from the inside of the bottle. If I shook them enough, and the stains were not obvious, they might pass Mayme’s merchantability test and be worth as much as three cents apiece at her grocery store. If the bottles did not clean up well, they went to the North market, Elmer’s Station, for two cents. I learned to maximize my profits by understanding the differentiated buyer’s market.

The money I earned from pop bottle collecting was usually invested in another market, baseball and football cards. Even as a child I sought “diversification and balance” in my collection keeping players from every team. I enjoyed organizing according to position and appearance and reading and memorizing the statistics. When I was not spending time sorting and playing with the cards, I carried them in my back pocket tied by a rubber band with cover cards and team cards on the outside edges. I learned how to protect my favorite cards (this was the day before cards had value) by holding them out of any floor games. I learned that the cards that slid along the floor better lost their edge after being used several times. I wanted my favorites like Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris and Hank Aaron to hit the homer, but eventually the harder push would wear out the card and make them less desirable as a trading commodity. For that reason, I benched my favorites and played cards which I did not like very much such as Marv and Faye Thornberry. Willie, Roger, Harmon, Hank and the Mick were used as pinch hitters at appropriate times in the game, but it was Marv and Faye Thornberry that saw the floor action. Later in life I observed that my habit of saving the stars for special occasions was a technique used by major league managers to get the most out of aging stars. The aging stars did not play every day and sometimes only were put in the lineup in the hopes that their special magic would ignite a rally.

The money I earned from pop bottle collecting was usually invested in another market, baseball and football cards. Even as a child I sought “diversification and balance” in my collection keeping players from every team. I enjoyed organizing according to position and appearance and reading and memorizing the statistics. When I was not spending time sorting and playing with the cards, I carried them in my back pocket tied by a rubber band with cover cards and team cards on the outside edges. I learned how to protect my favorite cards (this was the day before cards had value) by holding them out of any floor games. I learned that the cards that slid along the floor better lost their edge after being used several times. I wanted my favorites like Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris and Hank Aaron to hit the homer, but eventually the harder push would wear out the card and make them less desirable as a trading commodity. For that reason, I benched my favorites and played cards which I did not like very much such as Marv and Faye Thornberry. Willie, Roger, Harmon, Hank and the Mick were used as pinch hitters at appropriate times in the game, but it was Marv and Faye Thornberry that saw the floor action. Later in life I observed that my habit of saving the stars for special occasions was a technique used by major league managers to get the most out of aging stars. The aging stars did not play every day and sometimes only were put in the lineup in the hopes that their special magic would ignite a rally.Each year in those halcyon days, fall would arrive and the World Series would be settled. Yes, it was usually the Yankees and not my Dodgers who prevailed. After each baseball season, my brother Mike, Jeff and Brian Lofberg, Jay Hoglin, David Boatz, Keith Finney, and other Humboldt friends would put away our baseball cards and began trading, collecting, and playing with our football card collections. We designed and played football slide games with the fall icons, learning how to push the best players through the line for a long run and claimed the great sweeps were impressive touchdowns. Jeff presented the most memorable play-by-play, describing the impressive qualities of each player in the most realistic sports terminology like radio announcers he listened to so often. Jeff later became a sports announcer in local radio stations. Like the baseball cards, the best football players often became worn out prematurely because of hard use with our floor games. We often traded to get a back-up card of our favorites. Players like Jim Brown, Jim Taylor, and Paul Hornung were among my favorites. I still have a few of the old classics and the collection grew enormously in the 90's when it became the “family hobby.” Today I still own an almost perfect card of Paul Horning of the Green Bay Packers, my favorite football player before our Minnesota Vikings entered the league in the early sixties. I am aware that the card is worth about twenty-five dollars in many card-trading and selling markets. Being the conservative investor that I am, I am going to continue to hold the card until the Pack is back on top. I expect that the Hornung and Taylor cards will rebound in price, which is based upon past empirical research.

As I look back on my pop bottle and card trading days, I realize how I am indebted to the lessons I learned about the operation of the market. My present profession requires personal qualities such as negotiation, sales, and discretion. The lessons I learned from Mayme and Elmer were to be honest, have clear guidelines and refrain from taking advantage of those with less knowledge or experience. I carried over these qualities from my card trading experiences. I remember asking younger kids like Keith Finney, Danny Turner, or Guy Getschell whether the deal was good for them as well. In every trade, I always asked if they were certain that they wanted to trade a given card or cards for the one I wanted. My professional reputation as a trader was at stake. In a small town or in a large city, your professional reputation is your stock in trade. The most important lesson I learned was about the morality of the marketplace. Six principles were learned from the pop bottle business and trading in baseball and football cards: (1). Work hard to get ahead and don't be afraid to get dirty once in a while. (2). Save and invest, do not consume all that you earn and you will get ahead. (3). Develop a keen eye for the best players and trade old stars for the rookies that appear to be doing well. (4). Too much greed is not good for business; (5). Be broadly diversified and balanced. Just as you should not have baseball or football preferences for too many teams, choose selective sectors of the market based upon research and (6). Just as you should never discard a baseball or football card of a legend, don’t give up on the market. Never give up, stay in the market, and be cautious about throwing in the towel during market corrections. Eventually the market will always be higher, just like the value of the old sports rookie card. I learned business principles and lessons from collecting pop bottles along the roadsides near Humboldt, wisdom from time spent quietly visiting with Elmer Maxwell and Mayme Jury and prudence from the management of the few cents I acquired, investing in sports cards. As I reflect upon the business principles, lessons, wisdom, and prudence, they are striking similar to advice I give to clients today.

Editor's Note: Anthony [Tony] Rustad works as a financial advisor in Grand Forks, ND

Hi. My wifes name is Helena Wink, just as your pioneer doctor. Wink is a quit unusual name. The could be relatives. Do you have anything more to tell about her.

ReplyDeleteThe best regards, Joakim Sandberg, Sweden.

joakim.sandberg@svt.se