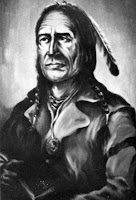

For the beleaguered Red River colonists, who were having trouble becoming self-sufficient in a landscape harsh and alien to them, the summer of 1816 turned into the nadir of their New World experience. On June 19, simmering tensions between the Hudson's Bay Company and the North West Company exploded in a battle at Seven Oaks, which saw twenty-one men die and shattered the confidence of the Scottish settlers, who were caught in the hatred between the rival fur-trade companies and were targets of Métis animosity. Now the weather would not cooperate. Since their arrival near the forks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers in 1812, they had had trouble making the most of the region's fertility. The 1812 harvest, for instance, was so poor that they were forced to journey 100 kilometers south to the better-supplied post at Pembina under the friendly guidance of Peguis, chief of the Ojibway. In 1813, they again wintered in Pembina.

For the beleaguered Red River colonists, who were having trouble becoming self-sufficient in a landscape harsh and alien to them, the summer of 1816 turned into the nadir of their New World experience. On June 19, simmering tensions between the Hudson's Bay Company and the North West Company exploded in a battle at Seven Oaks, which saw twenty-one men die and shattered the confidence of the Scottish settlers, who were caught in the hatred between the rival fur-trade companies and were targets of Métis animosity. Now the weather would not cooperate. Since their arrival near the forks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers in 1812, they had had trouble making the most of the region's fertility. The 1812 harvest, for instance, was so poor that they were forced to journey 100 kilometers south to the better-supplied post at Pembina under the friendly guidance of Peguis, chief of the Ojibway. In 1813, they again wintered in Pembina.In 1816, Peguis came to their rescue once more. This time he took the struggling settlers to his village at Netley Creek, sixty kilometers north of present-day Winnipeg. They were not to know what global conditions were making their sojourn so fraught, but in 1819 HBC trader and Red River surveyor Peter Fidler observed:

Within these last 3 years the climate seems to be greatly changed the summers being so backward with very little rain & even snow in Winter much less than usual and the ground parched up that all kinds of grass is very thin & short & most all the small creeks that flowed with plentiful streams all summer have entirely dried up after the snow melted away in the spring.... Wheat, Barley, & potatoes have been cultivated here a few years back to a considerable extent last summer a considerable quantity was sown & planted of the kinds above mentioned but owing to the very dryness of the season not even a single stalk was reaped or potatoes taken up and here before when showery summers the wheat would produce above 40 Barley 45 and the potatoes 50 fold. Even all the smaller Kinds of vegetables failed from the same cause but the first week in August last clouds of Grasshoppers came & destroyed what little barley especially had escaped the drought.The world the Selkirk settlers knew was a cooler one than our own. They were living in the Little Ice Age, the interval between the 1450 and 1850 when global temperatures were between 1.0 and 2.0[degrees]c cooler than they are now. Within that, the settlers were living in what some climatologists say was a cooling trend between 1809 and 1820. And in the middle of that came the 1815 eruption of Tambora. For settlers living on the edge of existence on the central North American plains, its effects were very nearly the last straw...

- From Volcano Weather: The Story of 1816, The Year Without a Summer by Henry Stommel and Elizabeth Stommel. Seven Seas Press, Newport, Rhode Island, 1983.

No comments:

Post a Comment