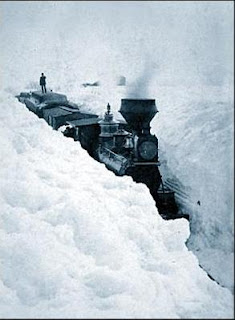

PHOTO: ELMER & TENNEY OF A SNOW BLOCKADE IN S. MINNESOTA, MARCH 29, 1881

Although the following article (from City Pages) is about the entire state of Minnesota, and not just St. Vincent, it focuses on one distinctive and major factor in living here (especially for our ancestors), the weather - in particular,

By Mike Mosedale

Admit it: Like most Minnesotans, you think our long, cold winters have made you a tougher and more virtuous person. This is a leading article of faith here. It lies at the core of Minnesota's identity. Exposure to an Alberta clipper, the magical thinking goes, works as some sort of anesthetic on the id. It protects you from the slide into turpitude and indolence that is characteristic of the warmer climes. It strengthens your resolve and purpose. And, most importantly, it promotes stoicism and common sense--those greatest of Midwestern virtues. After all, without those qualities, how can you possibly get the car unstuck from the snowdrift?

Perhaps you don't really believe this. Even so, you probably still do all you can to cultivate the notion. Say it's mid-January. You are on the telephone with a friend in California who says, "Things are great here"--at the moment, the lucky bastard is in the backyard in Malibu, playing horseshoes in stocking feet, sipping a fruity cocktail--and then asks, "So, how's it going in Minnesota?"

What are you going to say? Will you reply truthfully that you are awfully happy that you signed up for digital cable, because it is horrid outdoors and you haven't left the house of your own volition for six weeks and now you have Cinemax, so you didn't really see the need? Or will you say that you really enjoy a nose full of frozen snot? That you consider grime-blackened mountains of plowed snow things of beauty?

Of course not. Instead, like generations of Minnesotans before you, you will claim ruggedness. Perhaps you will do this subtly. Maybe you observe in passing that we Minnesotans actually drive our cars on frozen lakes--even though you know it is much less daring and impressive than it sounds. Truth be told, driving on lake ice in the middle of winter is not much different from driving in the snow-covered parking lot of a bankrupt mall. Or maybe you will find some graceful way to make mention of some of the frighteningly low temperatures recorded here. (Helpful reminder: The 60 below mark was set in Tower in the winter of 1996. And, no, you weren't there). And if you are feeling especially bold, you might even invoke the most cherished component of the Myth of Minnesota Exceptionalism: Sure, it's cold here, but that keeps the riffraff out.

Of course, there is lots of riffraff in Minnesota. You can confirm this with a visit to any of our many prisons, sports venues, government offices, or churches. Climatologically speaking, it is true that Minnesota winters are nasty, brutish, and long. But if you care to be honest, you have to admit something else: The hardships of the Minnesota winter have been so softened by technology, by the designs of our cities and suburbs and cars and homes, by our colossal commitment to making the Great Indoors ever more cushy, as to be rendered all but unrecognizable.

What is true is this: In the bad old days, winters here used to be very, very hard. The season did more than merely bollix up the daily commute (the true epicenter of most Minnesotans' grudge against winter). Once upon a time, winter meant more than an extra 15 minutes stuck in traffic in a car with heated seats, a CD player, and a good excuse for getting to work late.

What is true is this: In the bad old days, winters here used to be very, very hard. The season did more than merely bollix up the daily commute (the true epicenter of most Minnesotans' grudge against winter). Once upon a time, winter meant more than an extra 15 minutes stuck in traffic in a car with heated seats, a CD player, and a good excuse for getting to work late.

Consider the Minnesota of the early 19th century, a Minnesota that was not yet a state but rather a forlorn outpost inhabited by only the Dakota, the Ojibwe, fur traders, soldiers at Fort Snelling [Editorial Note from Trish: Hey, what about the settlement around what would later be Pembina/St. Vincent? At this time, the trading post there was one of the earliest settlements in the state and the region!] , and, later, the first waves of settlers. Little House on the Prairie notwithstanding, the Minnesota winters of the 19th century were defined mainly by epic suffering and existential horror. It's all there in the historical record--the incidents of starvation, cannibalism, and madness.

In a February 1818 letter, Duncan Graham, a trader with the Hudson Bay Company who was stationed at Big Stone Lake, stated the horrors of the frontier winter as plainly as anyone before or since. "I have experienced more trouble, anxiety, and danger since the 18th of October last than in the whole course of my life before and I would not undergo as much again for all the beaver that went out of Hudson Bay in 10 years," Graham wrote. "I am in hopes to go straight to heaven as I have every reason to think that I have already been to purgatory.... I have given the place where I am the name of Hell on Earth as I can find no other name more becoming it."

So read on. Say a prayer for the dead. And stop your bitching once and for all, because this used to be a really, really hard place to spend a winter. It isn't anymore.

GROUNDHOG DAY: WINTER CUISINE ON THE FRONTIER

Naturally, the risk of freezing to death was a major concern for early Minnesotans. Reports of frostbite and self-amputation are common in the historic record. Mind-bending suffering seems to be the defining feature of the winter experience. The contemporary historian Bruce White relates a story of a fur trader named Charles Oakes [Ermatinger] who, suffering from frozen feet, arrived at a particularly horrific frontier-style remedy for his problem: "He asked for an awl, punctured his feet full of holes, and had the men pour them full of brandy. This, while it was excruciatingly painful, both at the time and afterwards, saved him his feet."

Naturally, the risk of freezing to death was a major concern for early Minnesotans. Reports of frostbite and self-amputation are common in the historic record. Mind-bending suffering seems to be the defining feature of the winter experience. The contemporary historian Bruce White relates a story of a fur trader named Charles Oakes [Ermatinger] who, suffering from frozen feet, arrived at a particularly horrific frontier-style remedy for his problem: "He asked for an awl, punctured his feet full of holes, and had the men pour them full of brandy. This, while it was excruciatingly painful, both at the time and afterwards, saved him his feet."

But the most persistent hazard of the Minnesota winter was not cold per se; it was starvation. Famine's specter haunted not just the trappers and frontiersmen who stumbled ill-equipped into this forsaken territory, but also the native inhabitants who knew it best. In the course of especially brutal winters, the Indians sometimes found themselves without adequate rations or game to pursue. Thomas G. Anderson, a trader and captain in the British Indian Service, observed the phenomenon firsthand while traipsing around western Minnesota at the start of the 19th century.

In his account of the experience, Personal Narrative of Captain Thomas G. Anderson: 1801-1810, Anderson told of one winter in which he holed up near the headwaters of the Minnesota River in the company of a band of Dakota Indians led by a Chief Red Thunder. The weather was especially harsh, and the Indians "were soon reduced to subsist on the old buffalo hides they used to sleep on." Ultimately, Anderson, who shared his stores of corn with Red Thunder, was himself scrounging for animal carcasses to eat.

One day one of [Red Thunder's] men found the head of an old buffalo, which some of his race had lost last summer, and with difficulty brought it home. We all rejoiced in our straitened circumstances at this piece of good luck. The big tin kettle was soon filled and boiling, with a view of softening it [the buffalo head] and scraping off the hair.

But boiling water and ashes would not stir a hair. We dried it in the hopes that we might burn the hair off; but in vain. We felt sadly disappointed, as we were on short rations, our corn supply drawing near an end...[After finding another dead buffalo--"dead but not quite stiff"] we managed to take his tongue and heart to our camp, which was in some old trader's wintering house. A groundhog was ready for supper.

[The next morning, after Anderson awoke for breakfast, the cook asked,] "Which will you have, Sir, tongue or heart?" This directed my eyes to the kettle, boiling over with a black bloody froth, with a sickening putrid smell. I bolted out of the house, leaving the men to smack their lips on heart and tongue, while I took the remnant of the groundhog to the open air.

WHAT IS THE BEST PORTION OF A MAN TO EAT?

The official keeping of weather records in Minnesota began in October 1819. Just a few months earlier, 118 soldiers from the U.S. Army's Fifth Infantry had traveled up the Mississippi River to Pike Island, so named after a Lieutenant Zebulon Pike "purchased" it from the resident Dakota 14 years earlier. Now, after a long delay, the soldiers had at last arrived with plans to build the

The official keeping of weather records in Minnesota began in October 1819. Just a few months earlier, 118 soldiers from the U.S. Army's Fifth Infantry had traveled up the Mississippi River to Pike Island, so named after a Lieutenant Zebulon Pike "purchased" it from the resident Dakota 14 years earlier. Now, after a long delay, the soldiers had at last arrived with plans to build the

first permanent military outpost in the Minnesota Territory, Fort Snelling.

From the outset, it was as though the weather gods had fired a warning blast across the prow of the invading hordes. The message: This place is not fit for human habitation. While November and December temperatures were typical, weather historians say, by January it turned "abnormally cold." That month, average temperatures hovered around zero degrees. By the end of winter, about 40 soldiers had perished, mainly from scurvy.

As it turned out, the 1820s proved to be among one of the nastiest decades for weather in Minnesota history. December 1822 remains the coldest December on record. Between February and March of 1826, there were two and three feet of snow on the western prairie. The bad weather hit the Sioux Indians particularly hard. E.D. Neill--the Presbyterian clergyman, founder of Macalester College, and author of the first history of Minnesota--provided an account of some of the most vivid horrors in his narrative, Occurrences In and Around Fort Snelling:

1819-1840.

Especially harsh, wrote Neill, was the winter of 1829. "At the time the buffaloes had gone far west, and so the Sioux pursued them to the west. Many of the Indians perished in a severe winter of starvation." In another passage laced with stark detail, Neill relates the experiences of one party of Sioux who found themselves stranded in a sudden blizzard:

The storm continued for three days, and provisions grew scarcer, for the party was 70 in number. At last, the stronger men, with a few pairs of snow shoes in their possession, started for a trading post 100 miles distant. They reached their destination half-alive, and the traders, sympathizing, sent for Canadians with supplies for those left behind. After great toil they reached the scene of distress and found many dead; and what was more horrible, the living feeding on the corpses of their relatives. A mother had eaten her own dead child, and a portion of her own father's arms. The shock to her nervous system was so great that she lost her reason. Her name was Tash-u-no-ta, and she was both young and good looking.

One day in September 1829, while at Fort Snelling, she asked Captain Jouett if he knew which was the best portion of a man to eat.... He replied with great astonishment, "No," and she then said, "The arms." She asked for a piece of his servant to eat, as she was nice and fat. A few days after this, she dashed herself from the bluffs near Fort Snelling into the river. Her body was found just above the mouth of the Minnesota, and decently interred by the agent.

CLOUD MAN OF LAKE CALHOUN: CAUGHT IN A BLIZZARD SO DREADFUL HE WANTED TO BECOME A FARMER

In his 1880 tome, Dakota Life in the Upper Midwest, the Minneapolis missionary Samuel W. Pond shed some light on the elemental questions raised by any historical consideration of the Minnesota winter: How the did Native Americans, without benefit of polypropylene long johns, survive the deep freeze? And, just as important, what did they think of their rugged way of life? Pond gets to the answer through a story from Cloud Man, or Maripa-wichashta, a nonhereditary chief who resided on the west shore of Lake Calhoun.

In his 1880 tome, Dakota Life in the Upper Midwest, the Minneapolis missionary Samuel W. Pond shed some light on the elemental questions raised by any historical consideration of the Minnesota winter: How the did Native Americans, without benefit of polypropylene long johns, survive the deep freeze? And, just as important, what did they think of their rugged way of life? Pond gets to the answer through a story from Cloud Man, or Maripa-wichashta, a nonhereditary chief who resided on the west shore of Lake Calhoun.

Cloud Man told Pond how he and a small party of fellow hunters had once traveled west in search of winter buffalo when they were suddenly overcome by "a storm so violent that they had no alternative but to lie down and wait for it to pass over." With nothing but scraps of dried buffalo meat and blankets, the hunters let themselves be covered by snow, and waited for the storm to pass. "In the meantime," Pond wrote, "Cloud Man could hold no communication with his buried companions, and knew not whether they were dead or alive." While he lay and suffered, Pond added, Cloud Man "had the leisure to reflect on the vicissitudes of a hunter's life." Just a year earlier, a Major Taliaferro at Fort Snelling had urged Cloud Man to take up farming as an alternative to the hunter-gatherer life.

When the blizzard cleared, he "extricated himself from his prison," and, one by one, located his hunting buddies. Miraculously, all had survived, although some were unable to walk. Shortly afterward, Cloud Man discovered the cruel irony of the experience. Without knowing it, he and his party of his hunters had hunkered down just a short distance from a camp where they could have taken shelter. For Cloud Man, that settled the matter. It would be best to take up the white man's ways, and so he set about trying to convince his fellow chiefs to abandon the chasing of game for the ho-hum life of farming.

His agrarian proselytizing was ill-fated. Despite Pond's estimation of the chief as a man of "superior discernment and of great prudence and foresight," Cloud Man failed to persuade his fellow chiefs. He was killed in the great Dakota uprising in 1862.

As to Pond, he himself managed to endure the privations of Minnesota's winter, relying on his grit and stoicism. On one missionary trek to Lac qui Parle, Pond traveled through storms by day, and slept at night with nothing but the clothes on his back and a buffalo skin. "We did not expect to be comfortable," he wrote. "If we could avoid freezing, it was all we hoped for."

I AM THE MOST UNFORTUNATE OF HUMAN BEINGS: THE DIARY OF MARTIN MCLEOD

In 1836, Martin McLeod, an adventurous 23-year-old from Montreal, set out on a journey across the Great Plains as a foot soldier in one of the strangest crackpot ventures in 19th-century American history: "General" James Dickson's scheme to recruit an army of mixed-blood soldiers from Red River Valley, lead them into battle in a war for Texas independence, and ultimately form an Indian kingdom in California. Naturally, according to the plan, Dickson would preside over the new kingdom.

In 1836, Martin McLeod, an adventurous 23-year-old from Montreal, set out on a journey across the Great Plains as a foot soldier in one of the strangest crackpot ventures in 19th-century American history: "General" James Dickson's scheme to recruit an army of mixed-blood soldiers from Red River Valley, lead them into battle in a war for Texas independence, and ultimately form an Indian kingdom in California. Naturally, according to the plan, Dickson would preside over the new kingdom.

Not surprisingly, his grandiosity ran smack into the harsh, unromantic reality of the northern plains winter. McLeod, who proved to be one of Dickson's less hapless recruits, provided a harrowing account of his experiences traveling with a small contingent of Dickson's men (referred to as Mr. P and Mr. H) in the vicinity of Lac qui Parle:

March 7. Last night excessively cold. Today unable to leave camp. So stormy that it is impossible to see the distance of 10 yards on the plain...such are the disadvantages encountered by the traveler in this gloomy region at this inclement season.

March 14. Last night so cold could not get a moment's sleep. Today in camp, guide unable to go on, with sore eyes.

March 17. Suddenly, about 11 o'clock, a storm from the north came that no pen can describe. I perceived [Mr. H, one of my three traveling companions] to stoop, probably to arrange the strings of his snow shoes. In an instant afterwards, an immense cloud of drifting snow hid him from view and I saw him no more.

Saturday 18. Never was light more welcome to a mortal. At dawn, I crept from my hole and soon afterward heard cries. Fired two shots; soon after guide came up; he escaped by making a fire, and being a native and a half blood, his knowledge of the country and its dangers saved him. Mr. P was found with both his legs and feet frozen. All search for Mr. H proved ineffectual.

Sunday 19. ...Left Mr. P with all our blankets and robes except a blanket each (guide and myself), also plenty of wood cut, and ice near his lodge to make water of. Out of provisions. Obliged to kill one of our dogs; dog meat excellent eating.

April 2. This morning the two men [who were sent to retrieve Mr. P] returned. Poor P is no more. They found him in his hut, dead. He had taken off the greater part of his clothes, no doubt in a delirium caused by the excruciating pain of his frozen feet. In the hut was found nearly all the wood, his food, and a kettle of partially frozen water.

14 April. Embarked at sun rise in a canoe with Indians and squaws who are going to...Fort Snelling. Have for company 10 Indians and squaws in three canoes. These people have in one of their canoes the bodies of two of their deceased relatives which they intend to carry to a lake near the Mississippi more than 100 miles away.

1837 entry: I am the most unfortunate of human beings.

Unlike General Dickson, who vanished from history not long afterward, McLeod went on to lead a life of distinction. He became a prominent leader in Minnesota's territorial legislature. He had a county named after him. Still, he died an alcoholic wreck. Today he probably would have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder--a classification that likely would have applied to almost anyone who survived those hellish winters on the frontier.

"THEY WERE SOMEWHAT CONSUMED BY WILD ANIMALS"

If you page through 19th-century Minnesota newspapers, you will routinely encounter tales of blizzard survival--and, of course, tales of death. They are curious in tone, sometimes full of awe, sometimes utterly stoic and matter-of-fact. Take Kate E. Sperry's recollection of an 1865 blizzard in Martin County, originally published in the Fremont Sentinel. "All the old settlers will remember this one, as it was the one the Presslers were caught in, coming home from school. One of the boys had both legs and arms taken off by Dr. Winch, the famous Blue Earth Surgeon."

If you page through 19th-century Minnesota newspapers, you will routinely encounter tales of blizzard survival--and, of course, tales of death. They are curious in tone, sometimes full of awe, sometimes utterly stoic and matter-of-fact. Take Kate E. Sperry's recollection of an 1865 blizzard in Martin County, originally published in the Fremont Sentinel. "All the old settlers will remember this one, as it was the one the Presslers were caught in, coming home from school. One of the boys had both legs and arms taken off by Dr. Winch, the famous Blue Earth Surgeon."

Or consider Lt. Charles Stewart Peterson's straightforward recounting of the grim toll exacted by "the Historic Minnesota Blizzard of January 7 and 8, 1873." The blizzard, which the St. Paul Dispatch described as "unparalleled in our recent history," took many people by surprise, as it was immediately proceeded by unusually pleasant January weather. Peterson's characterizations of how people perished in the tempest are presented in staccato manner. Mostly, they consist of single sentences, devoid of any overt sentimentality or emotional comment. Taken together, though, they convey the horror of the storm with a brutal, if artless, efficiency:

A person named Wolverton froze to death in Mankato. Eight persons froze to death between Madelia and St. James. At St. James a man and a boy were victims. At Madelia, a woman went in search of her husband and both succumbed to the cold. At New Ulm, a man sought a doctor for his wife and newborn baby boy and all three froze to death. Seventeen coffins were used at New Ulm to bury those frozen dead. Thirteen were frozen to death at Lake Hensky six miles from Lake Crystal. Six school children froze to death between Fort Ridgely and Beaver Falls. Thomas Johnson, a farmer, froze to death near Evansville in northern Minnesota. A man froze to death near Stony Brook ten miles from Pomme de Terre....

In Otter Tail County, five persons near St. Olaf froze to death, mostly Norwegian farmers. Four miles west of Granger in Fillmore County, Reverend Evans was returning home with his wife and two children and came within three fourths of a mile of his home and was stranded in the snow. He carried one child home and returned for another and left with it. They were both lost, and the child at home and the mother left in the sleigh were both frozen to death.

One of the more compelling newspaper stories from 1866 concerned a Captain Fields, who was the commander of a cavalry detachment. In late February, Fields set out from the Coteau Prairie--a bedrock formation that straddles South Dakota, North Dakota, and Minnesota--destined for Sauk Centre. On the Coteau, Fields and his men encountered another company of soldiers, who were led by a Lieutenant Stevens and bound for Fort Wadswoth. Shortly after the two groups split, a severe storm set in. Stevens followed Fields's tracks for a spell, before conditions became so brutal he was forced to set up camp. That night, Stevens reported, fives mules perished in the cold and twelve of his men were "so badly frozen as to be unable to stand or walk."

One of the more compelling newspaper stories from 1866 concerned a Captain Fields, who was the commander of a cavalry detachment. In late February, Fields set out from the Coteau Prairie--a bedrock formation that straddles South Dakota, North Dakota, and Minnesota--destined for Sauk Centre. On the Coteau, Fields and his men encountered another company of soldiers, who were led by a Lieutenant Stevens and bound for Fort Wadswoth. Shortly after the two groups split, a severe storm set in. Stevens followed Fields's tracks for a spell, before conditions became so brutal he was forced to set up camp. That night, Stevens reported, fives mules perished in the cold and twelve of his men were "so badly frozen as to be unable to stand or walk."

After the storm cleared, soldiers located three of the horses from Fields's company. The bodies of the men, however, wouldn't be found for nearly three months, and their fate became a source of running concern in the Minnesota newspapers. As described in the May 10, 1866 issue of the St. Cloud Democrat, it didn't take long for the recovery crew--which included Fields's father--to piece together the doomed detachment's final episode of suffering:

"Within sight of timber where they knew was shelter, and possibly friends, they fell exhausted, frozen, into the cold embrace of death," the newspaper reported. "They were somewhat consumed by wild animals. Mr. Fields identified his son by his clothing, and it was heart rending to witness the anguish of the bereaved parent."

Thanks to Alan R. Woolworth and the Minnesota Historical Society for assistance in researching this story.

No comments:

Post a Comment