Plain of Roses. — A Desert Filter. — Making Pimmi-kon. — Canine Camp-followers. — Dry Dance Mountain. — Vigils of the Braves. — Death at the Feast. — Successful Ambush. — The Scalp Dance. — A Hunter's Appetite. — The Grand Chase. — Marking the Game. — Head over Heels. — Sketching under Difficulties. — A Troublesome Tenant.

Plain of Roses. — A Desert Filter. — Making Pimmi-kon. — Canine Camp-followers. — Dry Dance Mountain. — Vigils of the Braves. — Death at the Feast. — Successful Ambush. — The Scalp Dance. — A Hunter's Appetite. — The Grand Chase. — Marking the Game. — Head over Heels. — Sketching under Difficulties. — A Troublesome Tenant.I ARRIVED at Fort Garry about three days after the half-breeds had departed ; but as I was very anxious to witness buffalo hunting, I procured a guide, a cart for my tent, and a saddle horse for myself, and started after one of the bands. We travelled that day about thirty miles, and encamped in the evening on a beautiful plain covered with innumerable small roses. The next day was anything but pleasant, as our route lay through a marshy tract of country, in which we were obliged to strain through a piece of cloth all the water we drank, on account of the numerous insects, some of which were accounted highly dangerous, and are said to have the power of eating through the coats of the stomach, and causing death even to horses.

The next day I arrived at the Pambinaw [Pembina] River, and found the band cutting poles, which they are obliged to carry with them to dry the meat on, as, after leaving this, no more timbered land is met with until the three bands meet together again at the Turtle Mountain, where the meat they have taken and dried on the route is made into pim-mi-kon. This process is as follows: — The thin slices of dried meat are pounded between two stones until the fibres separate; about 501bs. of this are put into a bag of buffalo skin, with about 401bs. of melted fat, and mixed together while hot, and sewed up, forming a hard and compact mass; hence its name in the Cree language, pimmi signifying meat, and kon, fat. Each cart brings home ten of these bags, and all that the half-breeds do not require for themselves is eagerly bought by the Company, for the purpose of sending to the more distant posts, where food is scarce. One pound of this is considered equal to four pounds of ordinary meat, and the pimmi-kon keeps for years perfectly good exposed to any weather.

I was received by the band with the greatest cordiality. They numbered about two hundred hunters, besides women and children. They live, during these hunting excursions, in lodges formed of dressed buffalo skins. They are always accompanied by an immense number of dogs, which follow them from the settlements for the purpose of feeding on the offal and remains of the slain buffaloes. These dogs are very like wolves, both in appearance and disposition, and, no doubt, a cross breed between the wolf and dog. A great many of them acknowledge no particular master, and are sometimes dangerous in times of scarcity. I have myself known them to attack the horses and eat them.

Our camp broke up on the following morning, and proceeded on their route to the open plains. The carts containing the women and children, and each decorated with some flag, or other conspicuous emblem, on a pole, so that the hunters might recognise their own from a distance, wound off in one continuous line, extending for miles, accompanied by the hunters on horseback. During the forenoon, whilst the line of mounted hunters and carts were winding round the margin of a small lake, I took the opportunity of making a sketch of the singular cavalcade.

The following day we passed the Dry Dance Mountain [aka Dry Dance Hill or Ne-Jank-wa-win], where the Indians, before going on a war party, have a custom of dancing and fasting for three days and nights. This practice is always observed by young warriors going to battle for the first time, to accustom them to the privations and fatigues which they must expect to undergo, and to prove their strength and endurance. Should any sink under the fatigue and fasting of this ceremony, they are invariably sent back to the camp where the women and children remain.

Pembina Mountain rises on the north and east in a series of table-lands, each table about half a mile in width, sparsely timbered, and bountifully supplied with springs. On its western slope, at the base of which runs the Pembina River, the mountain terminates abruptly. Across the stream, flowing deep below the surface in a narrow valley, the banks remain of about an equal height with the mountain, stretching away toward the Missouri in a bare, treeless plain, broken only by the solitary elevation in the dim distance of Ne-Jank-wa-win (Dry Dance Hill). - From A Great Buffalo "Pot-Hunt" by H.M. RobinsonAfter leaving this mountain, we proceeded on our route without meeting any buffalo, although we saw plenty of indications of their having been in the neighbourhood a short time previously. On the evening of the second day we were visited by twelve Sioux chiefs, with whom the half-breeds had been at war for several years. They came for the purpose of negotiating a permanent peace, but, whilst smoking the pipe of peace in the council lodge, the dead body of a half-breed, who had gone to a short distance from the camp, was brought in newly scalped, and his death was at once attributed to the Sioux. The half-breeds, not being at war with any other nation, a general feeling of rage at once sprang up in the young men, and they would have taken instant vengeance, for the supposed act of treachery, upon the twelve chiefs in their power, but for the interference of the old and more temperate of the body, who, deprecating so flagrant a breach of the laws of hospitality, escorted them out of danger, but, at the same time, told them that no peace could be concluded until satisfaction was had for the murder of their friend. Exposed, as the half-breeds thus are, to all the vicissitudes of wild Indian life, their camps, while on the move, are always preceded by scouts, for the purpose of reconnoitring either for enemies or buffaloes. If they see the latter, they give signal of such being the case, by throwing up handfuls of dust; and, if the former, by running their horses to and fro.

Three days after the departure of the Sioux chiefs, our scouts were observed by their companions to make the signal of enemies being in sight. Immediately a hundred of the best mounted hastened to the spot, and, concealing themselves behind the shelter of the bank of a small stream, sent out two as decoys, who exposed themselves to the view of the Sioux. The latter, supposing them to be alone, rushed upon them, whereupon the concealed half-breeds sprang up, and poured in a volley amongst them, which brought down eight. The others escaped, although several must have been wounded, as much blood was afterwards discovered on their track. Though differing in very few respects from the pure Indians, they do not adopt the practice of scalping ; and, in this case, being satisfied with their revenge, they abandoned the dead bodies to the malice of a small party of Saulteaux who accompanied them.

The Saulteaux are a band of the great Ojibeway nation, both words signifying "the Jumpers," and derive the name from their expertness in leaping their canoes over the numerous rapids which occur in the rivers of their vicinity. I took a sketch of one of them, Peccothis, "the Man with a Lump on his Navel." He appeared delighted with it at first ; but the others laughed so much at the likeness, and made so many jokes about it, that he became quite irritated, and insisted that I should destroy it, or, at least, not show it as long as I remained with the tribe.

The Saulteaux, although numerous, are not a warlike tribe, and the Sioux, who are noted for their daring and courage, have long waged a savage war on them, in consequence of which the Saulteaux do not venture to hunt in the plains except in company with the half-breeds. Immediately on their getting possession of the bodies, they commenced a scalp dance, during which they mutilated the bodies in a most horrible manner. One old woman, who had lost several relations by the Sioux, rendered herself particularly conspicuous by digging out their eyes and otherwise dismembering them.

The following afternoon, we arrived at the margin of a small lake, where we encamped rather earlier than usual, for the sake of the water. Next day I was gratified with the sight of a band of about forty buffalo cows in the distance, and our hunters in full chase ; they were the first I had seen, but were too far off for me to join in the sport. They succeeded in killing twenty-five, which were distributed through the camp, and proved most welcome to all of us, as our provisions were getting rather short, and I was abundantly tired of pimmi-kon and dried meat. The fires being lighted with the wood we had brought with us in the carts, the whole party commenced feasting with a voracity which appeared perfectly astonishing to me, until I tried myself, and found by experience how much hunting on the plains stimulates the appetite.

The upper part of the hunch of the buffalo, weighing four or five pounds, is called by the Indians the little hunch. This is of a harder and more compact nature than the rest, though very tender, and is usually put aside for keeping. The lower and larger part is streaked with fat and is very juicy and delicious. These, with the tongues, are considered the delicacies of the buffalo. After the party had gorged themselves with as much as they could devour, they passed the evening in roasting the marrow bones and regaling themselves with their contents.

For the next two or three days we fell in with only a single buffalo, or small herds of them; but as we proceeded they became more frequent. At last our scouts brought in word of an immense herd of buffalo bulls about two miles in advance of us. They are known in the distance from the cows, by their feeding singly, and being scattered wider over the plain, whereas the cows keep together for the protection of the calves, which are always kept in the centre of the herd. A half-breed, of the name of Hallett, who was exceedingly attentive to me, woke me in the morning, to accompany him in advance of the party, that I might have the opportunity of examining the buffalo whilst feeding, before the commencement of the hunt. Six hours' hard riding brought us within a quarter of a mile of the nearest of the herd. The main body stretched over the plains as far as the eye could reach. Fortunately the wind blew in our faces : had it blown towards the buffaloes, they would have scented us miles off.

I wished to have attacked them at once, but my companion would not allow me until the rest of the party came up, as it was contrary to the law of the tribe. We, therefore, sheltered ourselves from the observation of the herd behind a mound, relieving our horses of their saddles to cool them. In about an hour the hunters came up to us, numbering about one hundred and thirty, and immediate preparations were made for the chase. Every man loaded his gun, looked to his priming, and examined the efficiency of his saddle-girths.

The elder men strongly cautioned the less experienced not to shoot each other; a caution by no means unnecessary, as such accidents frequently occur. Each hunter then filled his mouth with balls, which he drops into the gun without wadding; by this means loading much quicker and being enabled to do so whilst his horse is at full speed. It is true, that the gun is more liable to burst, but that they do not seem to mind. Nor does the gun carry so far, or so true ; but that is of less consequence, as they always fire quite close to the animal.

Everything being adjusted, we all walked our horses towards the herd. By the time we had gone about two hundred yards, the herd perceived us, and started off in the opposite direction at the top of their speed. We now put our horses to the full gallop, and in twenty minutes were in their midst. There could not have been less than four or five thousand in our immediate vicinity, all bulls, not a single cow amongst them.

The scene now became one of intense excitement ; the huge bulls thundering over the plain in headlong confusion, whilst the fearless hunters rode recklessly in their midst, keeping up an incessant fire at but a few yards' distance from their victims. Upon the fall of each buffalo, the successful hunter merely threw some article of his apparel — often carried by him solely for that purpose — to denote his own prey, and then rushed on to another. These marks are scarcely ever disputed, but should a doubt arise as to the ownership, the carcase is equally divided among the claimants.

The chase continued only about one hour, and extended over an area of from five to six square miles, where might be seen the dead and dying buffaloes, to the number of five hundred. In the meantime my horse, which had started at a good run, was suddenly confronted by a large bull that made his appearance from behind a knoll, within a few yards of him, and being thus taken by surprise, he sprung to one side, and getting his foot into one of the innumerable badger holes, with which the plains abound, he fell at once, and I was thrown over his head with such violence, that I was completely stunned, but soon recovered my recollection. Some of the men caught my horse, and I was speedily remounted, and soon saw reason to congratulate myself on my good fortune, for I found a man who had been thrown in a similar way, lying a short distance from me quite senseless, in which state he was carried back to the camp.

I again joined in the pursuit; and coming up with a large bull, I had the satisfaction of bringing him down at the first fire. Excited by my success, I threw down my cap and galloping on, soon put a bullet through another enormous animal. He did not, however, fall, but stopped and faced me, pawing the earth, bellowing and glaring savagely at me. The blood was streaming profusely fusely from his mouth, and I thought he would soon drop. The position in which he stood was so fine that I could not resist the desire of making a sketch. I accordingly dismounted, and had just commenced, when he suddenly made a dash at me. I had hardly time to spring on my horse and get away from him, leaving my gun and everything else behind.

When he came up to where I had been standing, he turned over the articles I had dropped, pawing fiercely as he tossed them about, and then retreated towards the herd. I immediately recovered my gun, and having reloaded, again pursued him, and soon planted another shot in him ; and this time he remained on his legs long enough for me to make a sketch. This done I returned with it to the camp, carrying the tongues of the animals I had killed, according to custom, as trophies of my success as a hunter.

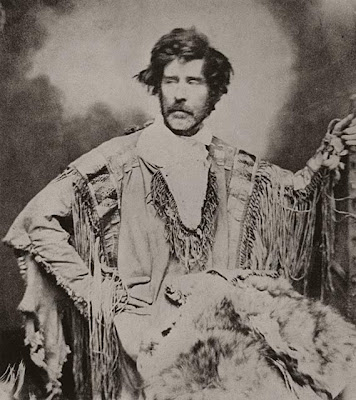

|

| PAUL KANE |

I have often witnessed an Indian buffalo hunt since, but never one on so large a scale. In returning to the camp, I fell in with one of the hunters coolly driving a wounded buffalo before him. In answer to my inquiry why he did not shoot him, he said he would not do so until he got him close to the lodges, as it would save the trouble of bringing a cart for the meat. He had already driven him seven miles, and afterwards killed him within two hundred yards of the tents. That evening, while the hunters were still absent, a buffalo, bewildered by the hunt, got amongst the tents, and at last got into one, after having terrified all the women and children, who precipitately took to flight. When the men returned they found him there still, and being unable to dislodge him, they shot him down from the opening in the top.

From Wanderings of an Artist Among the Indians of North America, by Paul Kane